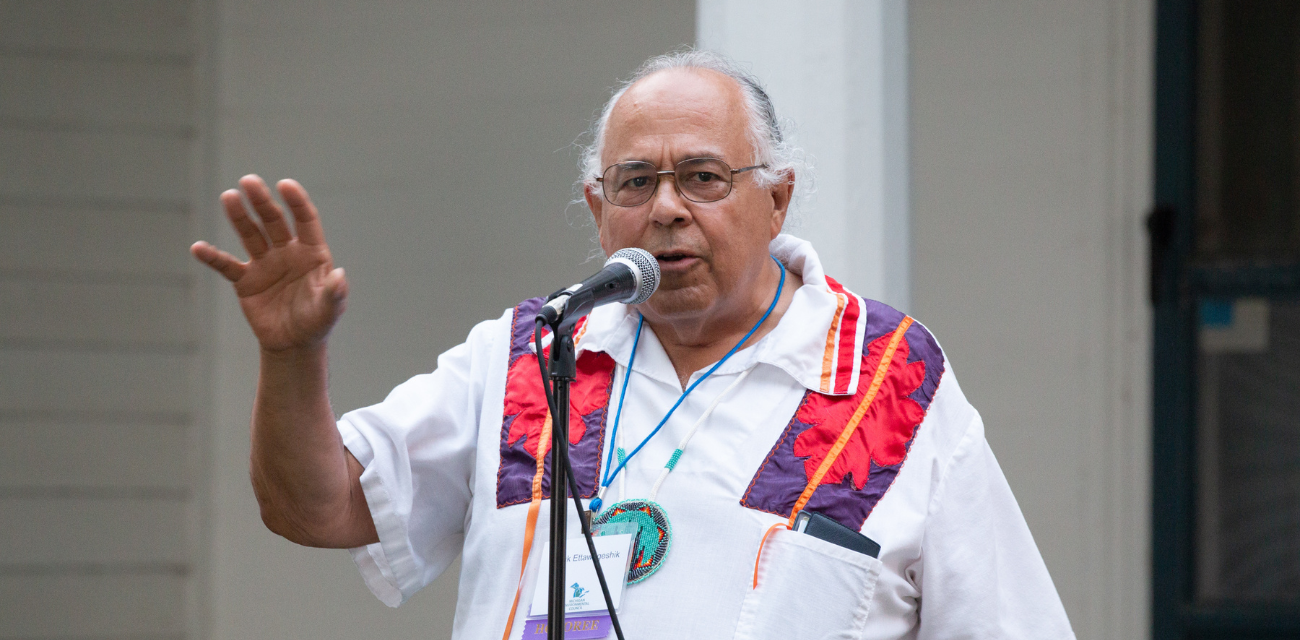

Frank Ettawageshik: 2021 Milliken Award winner

Authored by

Little Traverse Bay Band citizen has made the planet better for future generations

While an origin story like this is always debatable, Frank Ettawageshik is certain he’s at least had some role in it.

It was summer 2005. Ettawageshik was in Duluth, Minnesota, with fellow leaders from local, state and federal governments releasing a report on ways to best protect Great Lakes ecosystems. He represented Indigenous tribes as the chairman of the Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians.

Sometime during the summit, Ettawageshik spoke about a simple conservation practice: turning off the tap when brushing teeth.

Doing so, he said, means less water is used and less energy is generated to draw, move, dispose and purify it. Not a big deal if only one person does this, Ettawageshik admitted, but if everyone followed suit, the impact would be phenomenal.

“With 10 people, you can get more done,” he said 16 years later. “With a thousand or ten thousand people, you can get a lot done. And with a million people, think of how much you can get done.”

The teeth-brushing story is emblematic of the beliefs and ethos Ettawageshik has put into action for decades in the name of water and wildlife preservation, climate change protection, and tribal sovereignty.

In the face of devastation – flooding, water commodification and Native suppression – Ettawageshik says we must not fall into despair. We can feel small, but we must remember that everyone else feels small, too, and when small people take small actions together, they can make good changes that will be felt for generations.

This practical, big-picture perspective is what makes Ettawageshik special. He excels at rallying people together around a cause, often representing them in spaces they did not have access to before – state and federal government workgroups, tribal associations, binational Great Lakes compacts and the United Nations.

In these positions, Ettawageshik merges his policy and government expertise with an understanding of the people he represents to make our planet better for future generations.

In honor of his impact, Ettawageshik received the Helen & Milliken Distinguished Service Award from the Michigan Environmental Council at the 23rd Annual Environmental Awards Celebration in Dexter.

From Waganakising to the United Nations

Ettawageshik’s environmental activism began during his 16-year tenure as chairman of the Little Traverse Bay Little Traverse Bay Bands of Odawa Indians in Waganakising – or, in U.S. government terms, the Harbor Springs area.

When he accepted the role, the Little Traverse Bay Bands had $4,000 in the bank and a handful of employees.

With his fellow council members, the tribe completed a 158-year mission and reaffirmed its sovereign status with a signature from President Bill Clinton. Then, a decade later, the Tribe adopted a new Constitution that separated powers into executive, legislative and judicial branches.

By the time Ettawageshik stepped down as chairman, the Little Traverse Bay Bands had a $30 million budget, a health clinic, a more just and balanced government, stronger relations with other tribes and the United States, and plenty more staff. He helped bring better resources and voices to more than 5,000 members.

Along the way, Ettawageshik and others grounded the Little Traverse Bay Little Traverse Bay Bands in environmentally just policies that benefited not only the nation, but others.

“Laws become undone when they become inconvenient for too many people,” he said. “So we have to work really hard to protect lakes and have everybody get on board..This ecosystem, the Great Lakes, affects the whole country.”

The Little Traverse Bay Bands adopted a resolution that reflected the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, which are climate change commitments United Nations members have voluntarily committed to. More recently, the Little Traverse Bay Bands have cut back on its energy use and saved over 85,000 metric tons of carbon from being emitted in a 10-year span.

The Little Traverse Bay Bands also became a major player in binational decisions around the Great Lakes. When the United States and Canada left out Indigenous nations on Great Lakes preservation discussions, Ettawageshik and the Little Traverse Bay Bands were initiators and signatories in the Tribal and First Nations Great Lakes Water Accord.

It brought tribes into decision making on the Great Lakes Compact negotiated by the eight states of the Great Lakes Basin. It set strict standards on how the area’s groundwater and surface water could be withdrawn and diverted. Ettawageshik was part of the Indigenous caucus that advised the parties during negotiations. A parallel agreement was made between those same states and two Canadian provinces.

Now, Ettawageshik serves on the Michigan Water Use Advisory Council, which continues to recommend best ways to preserve and understand Michigan’s water.

Ettawageshik was also an appointee to the Great Lake Regional Collaboration, which called on and advocated for Great Lakes protection funding. Working for years with fellow appointees, their efforts finally paid off, leading to the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative’s creation, which has provided over $3.48 billion in federal funding to remove pollution, algal blooms and other threats.

A month ago, Ettawageshik was brought back into the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative’s fold when EPA Administrator Michael Regan appointed him to serve on the Great Lakes Advisory Board to help oversee the Initiative’s aims and actions.,

The pinnacle, perhaps, came at the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015. Ettawageshik and over 200 other Indigenous leaders were successful in amending the agreement so Indigenous rights and knowledge were considered in climate decisions. They also saw through their proposed climate change goal: keeping the global temperature within two degrees Celsius of pre-industrial levels.

The list of achievements goes on – president of the Association of American Indian Affairs, executive director of the United Tribes of Michigan. Each effort is grounded in getting Indigenous peoples at the decision-making table and providing insights and knowledge to make the world better for everyone – flora and fauna included.

Ettawageshik may serve as the appointed leader in all these endeavors, but he is quick to say it is other Indigenous peoples guiding him and working to implement good environmental practices grounded in Indigenous sovereignty and power.

“Frank has been tremendous in bringing Native people together,” said Dr. Kyle Whyte, University of Michigan professor and member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. “He’s created connectivity and networks and relationships across people who otherwise wouldn’t have otherwise had those relationships.”

Whyte first met Ettawageshik when they both served on an environmental justice task force created by former Gov. Rick Snyder. Ettawageshik’s leadership skills were immediately apparent – a man of ethics and integrity.

“Frank is diplomatic, but at the same time he stands up to people and institutions that are threatening the sanctity of the environment and the quality of the environment,” he said.

Walking softly on Mother Earth

Colleen Medicine first met Ettawageshik a few years back when she was working in the repatriation office of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, of which she’s a citizen of.

“It was probably intimidating for me as a 21-year-old to meet Frank,” she said with a chuckle. “He was almost like a celebrity.”

He has a wealth of knowledge, Medicine said. He has “huge” tenacity. And he has a hand in efforts as diverse as trail mix ingredients.

Medicine sees these traits again and again as the program director of the Association of American Indian Affairs, the nation’s oldest nonprofit protecting Indian Country sovereignty and culture. Ettawageshik is the board president.

“He’s really paved the path for people to come behind him, because he’s at tables that we’ve never traditionally got to be at,” she said.

In a way, Ettawageshik is making the world better for future generations both as a door-opener and a policy-maker.

Ettawageshik often speaks of this – descendance and ancestry – in the context of climate. He says our ancestors have gotten us to where we are now at this moment. We must do the same as they did: making sure our future generations are in as good a place as possible.

“Seven generations from now, my hopes are we have healthy waters, a healthy environment, prosperous communities, and safe, happy, healthy children,” he said. “It’s a fairly simple goal, and yet it is extremely difficult to get there.”

And yet, Ettawageshik – father of four, grandfather of eight, husband, artist, storyteller, Indigenous advocate and environmental activist – is well on his way.

Discover

Power environmental change today.

Your gift to the Michigan Environmental Council is a powerful investment in the air we breathe, our water and the places we love.

Sign up for environmental news & stories.

"*" indicates required fields